Influencers: The Pied Pipers of Our Time

Influencers are an unfortunate fact of modern society. While most people view them as harmless, they actually have a chilling ability to control social conversation, and alter offline behaviour.

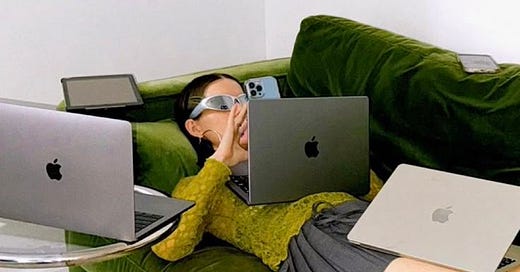

Every morning, the twinkling sound of my phone alarm wakes me at exactly 9:00. I roll through the bedsheets, blinded by sleep, and feel for my phone to switch off what surely must be the most irritating sound known to man. My interaction with my phone should end here, having fulfilled its function of arousing me. Instead, I choose to scroll on my phone for the next hour.

At the beginning of this stint of lost time, I justify it to myself by going through my Whatsapp messages. After about ten minutes, I flick over to Instagram. If my morning degenerates sufficiently, I can find myself on Tiktok before the clock has reached 10:00.

Like almost everyone else in my generation, I am victim to a humiliating and pathetic addiction. What makes this compulsive phone usage so degrading, however, is not the simple fact of using my phone, but the media that I choose to consume on it. If I spent an hour every morning watching a Cambridge Union debate on YouTube, I rather doubt I would roll out of bed with the same guilt that I do when I spend an hour on Instagram.

Ubiquitous across social media apps is the existence of influencers. This frankly Orwellian term describes individuals who amass large followings and earn an income by promoting products to their followers. In short, they aim to ‘influence’ their followers’ shopping habits. As the name would suggest, however, they have the power to manipulate a lot more than their followers’ spending.

Take the recent wellness boom among Gen Z as an example. Brands tend to select influencers to sell their products based on how easily marketable that influencer is. Individuals who amass large followings by broadcasting their political opinions, or controversial lifestyles may be popular among niche communities of followers, but it is those who show tame morning routines, or ‘Get Ready With Me’ videos that are chosen by enterprises to sell their product.

In part, this is because these influencers are less likely to fall into controversy due to their insipid content. Products also fit into inoffensive lifestyle videos because they depict how the product (whether it be an article of clothing, a skincare line or online therapy course) could fit into one’s life. As such, influencers who showcase their lifestyle routines are more likely to gain brand deals, earn money, and have their content boosted as a result.

This has led to hundreds of influencers being exalted to infamy for utter mediocrity. Mediocrity sells. A quick flit through TikTok will display dozens of videos of perfectly manicured women going to reformer pilates classes in their matching workout outfits, before settling down to a nutritionally impeccable yogurt bowl topped with every species of nut and berry under the sun. Oh, and lest we forget the obscure product of the month that you can buy - a spoonful of sea moss gel, for your daily collagen intake! Similarly, muscular men show themselves waking up at 5am, having a protein shake for breakfast and working on their business from home before immersing themselves in a cold plunge and promoting their favourite protein bar. And it works: across the board, nightclubs are shutting down in favour of pilates outlets, frequented by an army of young women in spandex leggings and sports bras of a uniform baby pink. Adolescent boys devise a strict regimen of protein intake and body building sessions at their local gym. This is but one example of how online activity is directly influencing the material lives of the youth.

Some would argue that a surge in the pursuit of wellness is a harmless -even positive- effect of influencers, and they may well be correct. What I find disturbing in this example is the fact that influencers have any impact at all upon real human behaviour offline.

A further, and doubtless more grave, example is the way in which influencers shape intellectual conversations. When you turn your vision to a mere generation ago, the public intellectuals that reigned supreme were of indisputable calibre. Oxbridge and Ivy League educated, well spoken, and witty, the likes of Stephen Fry, Christopher Hitchens, Steven Pinker and Susan Sontag were rightfully hailed as beacons of knowledge and ideas. In contemporary times, the scope of what is considered an intellectual has widened into a gaping cesspit, while the breadth of ideas discussed by these figures has narrowed.

TikTok and YouTube in particular have catapulted many such pseudo intellectuals into successful careers. The name Charlie Kirk is well known among my generation. Kirk is an American evangelical Christian and conservative, who took to organising debates on college campuses, in order to stimulate conversations he believed were being quietly shut down across academic arenas in the US.

While his goal of incentivising members of the youth to engage in discourse with which they do not align is admirable (and arguably essential, given the rise of students actively preventing conservative speakers and lecturers from engaging on campus debates) the ideas he presents are tediously repetitive, logically flawed, and, at times, objectively incorrect. The reach of his ideas, which become encapsulated into viralised clips on TikTok, typically spark a concoction of either hatred from left leaning students, or support from right wing or religious youth. Nevertheless, his videos, in being paid attention to en masse, dictate the breadth of cultural discourse that my generation has today.

A few weeks ago, Kirk was hosted at a Cambridge Union debate, where he spoke on issues such as religion, feminism and Trump’s foreign policies. Following this debate, many clips have been uploaded to TikTok, and videos of people either vouching for him or expressing disapproval have inundated the app. Yet the responses to Kirk’s arguments typically have to bend to the mistruths and enormous logical leaps of faith that he makes.

One of his most frequent arguments is that women in the West have become unhappier as a result of the pivot away from traditional family values and roles as we leave religion behind, and “replace” it with feminism. While it is true that women in the West are reporting greater rates of unhappiness than 50 years ago, the same is true of men, and to attribute this change to a shift away from religiosity is not only to make a wild assumption, but also to fall into the statistical error or interpreting correlation as causation.

When individuals on social media combat his ideas, they tend to point out that it is sexist and incorrect to claim that women were happier when they were subjected to stricter gender roles under the institution of marriage. By failing to point out his mistaken rationale and instead following his line of reasoning and objecting to that instead, they implicitly accept the argument as legitimate.

Yet, we live in a time where it is no longer necessary for women to become docile, domestic creatures. To fight against people who believe this is a loss of precious time, because we already live in the reality we are advocating for. Kirk’s beliefs reside on the fringe, but social media presents them as mainstream. As such, influencers such as Kirk are increasingly embroiling us in pseudo intellectual conversations which allow us to masquerade as well informed political activists, but in actuality, keep our society stagnant as the same topics and arguments are echoed infinitely. The time dedicated to such tired subjects is time diverted away from much more pressing matters: matters such as climate change, global superpower dynamics, immigration, and genocides.

That is not to say that issues such as feminism, abortion and free speech have no place at the table of intellectual conversation: on the contrary, these are issues which are currently very inflammatory in parts of the world, and merit discussion in order to draw on the problems people perceive in them. I only argue that these topics have taken a disproportionate amount of attention from the public, and that many people have already formed an opinion on them based on the widely broadcasted rationale from both sides of the debate. If new ideas or points of view are contributed, then they undoubtedly enrich pluralism in society. But to hear the same ideas repeatedly from different mouths does not serve any social function other than for those who repeat them to experience a brief period of thrill at being looked upon as an authority on the matter.

The phrase ‘echo chamber’ epitomises this dilemma perfectly. Social media algorithms deliberately push extremist content and ideas upon users, since these notions gain the most traction due to their inherent shock value. Influencers who discuss political and cultural matters are hence incentivised to advocate emphatically for unorthodox ideas in an ever tensing political game of tug of war. Both sides of the political spectrum showcase extreme attitudes online: the far right increasingly vouch for the reimposition of Christianity as a means for social cohesion (despite looking down upon theocracies in the Middle East), while the far left call for the social acceptance of trans women as biological women, despite this never having been a topic of serious debate prior to social media’s launch in the early 2010’s, and being simply untrue.

(I feel the need to clarify here that I do believe trans individuals should enjoy the same rights as any other member of society, but to claim that they are experiencing a physical change in sex when they are objectively not is damaging in a political context since certain policies are made to protect specific sexes)

The presentation of these ideas is often positioned in uniform ways, in a tediously repetitive manner, giving rise to the term ‘echo’ chamber. This usually reinforces the beliefs one already held, and works by extremifying the content millimetre by imperceptible millimetre until one holds ‘opinions’ which are simple mistruths. This is in large part because extremists often rely on the repetition of information as a substitute for the veracity of their claims. Most of us are familiar with the chilling example of 1930’s Germany, where constant lies were told to the public, who eventually internalised them as true, due to their relentless exposure to them.

Social media is not used as a tool to connect with others. Our society is suffering from a painful poverty of human connection and truth due to its sly crawl to the top as ruler of our collective attention. To wake up and watch a friend’s Instagram story is a pathetic and artificial substitute for meeting up with that same person for an afternoon coffee, and a four hour long conversation.

I am not proposing you delete your accounts, and completely resist the pull of that traitorous screen. But, if you must be a user, then dedicate a short period to sifting through the tides of garbage that float through TikTok, Instagram and YouTube. Shave down your following lists to include only your close friends, to cut out the exposure to influencer content - in essence, glorified adverts.

If you crave an intellectual debate, amputate the tumour of pseudo-intellectualism, and replace it with the healing therapy of stimulating discourse (I will include a list of my favourite debate and cultural conversation channels below).

You are not a compulsive money spender, nor a mere pawn in a political game. You are entitled to have tangible, concrete experiences offline, and interests formed by your own propensities to talent and curiosity. You are entitled to nuanced political ideas that may even fall on both sides of the political spectrum. Don’t accept the lie that has been sold to you, the lie that social media caters to your needs. Until you begin to use social media with careful intention, YOU cater to it, not the other way around.

Shouting from the rooftops in agreement with this. Love how you referred to it as being “exalted to infamy for utter mediocrity.”

Sex Sea ⛵